張廷壽《吊駱義烏墓》“Commemorating Luo Yiwu at his Tomb” by Zhang Tingshou

- Rachelle

- Dec 14, 2020

- 5 min read

文章正氣挾風霜,

莫恨當年宰相盲。

假使蛾眉能愛士,

千秋誰識駱賓王。[1]

The air of integrity in [his] writing carries wind and frost.

Don’t complain the prime ministers then were blind –

If the arched eyebrows [2] had been able to cherish [this] gentleman,

Who in the following millennia would know Luo Binwang?

[1] Red characters rhyme. [2] The word emei 蛾眉, literally “moth eyebrows,” represents a female’s long and arched eyebrows that resemble the antennae of a silkworm moth; for a nice picture of the antennae that perfectly explains this simile, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombyx_mori#/media/File:CSIRO_ScienceImage_10746_An_adult_silkworm_moth.jpg. In this poem, emei refers to Empress Dowager Wu Zetian; more on this later.

I didn’t know Luo Binwang 駱賓王 (619?-684?), one of the four eminent poets of the early Tang, was a native of Yiwu until I was about to go there to make a transfer from coach to train. I stayed near the Yiwu International Trade City, the world’s largest small commodities market. As I walked around in the vicinity, I was quite impressed by how dedicated to business this area is. Street after street I saw nothing but hotels, restaurants, and banks. There is a Luo Binwang Park located some six kilometres southwest of the trade city. I didn’t really have time to go there, but I had a surprising encounter with his work.

Nowadays, the most famous poem by Luo Binwang is definitely “Yong e” 詠鵝 (Ode to the goose), a poem every Chinese kid commits to memory in primary school. It’s said that Luo Binwang wrote it when he was only seven years old, which makes the simple poem a clear sign of his literary talent. When I sat down in the Wushang Noodle Restaurant 烏商麵館 (lit. “[Yi]wu Tradesmen Noodle Restaurant”), I saw this poem on the table, together with an image of the boy and two geese in a garden. It’s particularly interesting that the calligraphy on the table has three variants of the word e 鵝 (goose) for the first line of the poem, creating graphic liveliness for the repetition of sound.

鵝,鵞,䳘,

曲項向天歌。

白毛浮綠水,

紅掌拔清波。

Goose, goose, goose!

[They] bend their neck and sing towards the sky,

White hairs floating on green water,

Red palms pushing clear waves.

There is no doubt that the design of this tabletop can bring back childhood memories for many, and the locals must be proud to see the well-known work of their countryman. However, in literary history Luo Binwang is perceived quite differently from his image as a prodigy in modern popular culture. Instead, he is remembered as a poet who was skilled and courageous enough to draft the powerful denunciation of Empress Dowager Wu Zetian 武則天 (624-705, ruling 690-705) for Li Jingye 李敬業 (d. 684) who rose in rebellion in 684.[3] This official denunciation, written in crafted parallel prose (pianwen 駢文), criticises the lascivious behaviour and evil nature of Wu Zetian and openly challenges the legitimacy of her regency.

Following the failure of Li Jingye’s rebellion, Luo Binwang disappeared from the stage. Some said he died in the rebellion; some said he became a monk. But because of his denunciation of Wu Zetian, many writers paid respect to him in their works.[4] Their laudatory words rarely (if ever) mention Luo Binwang’s poem on the goose, but unanimously praise him for the denunciation, just as shown in Zhang Tingshou’s 張廷壽 (fl. 19th century) poem translated at the beginning of this blog.

Although Zhang Tingshou’s poem doesn’t contain the keyword “denunciation,” it alludes to a follow-up narrative about it. When Wu Zetian read Luo Binwang’s words against her, she was unhappy, understandably, at the beginning. But as she read on, she was very much impressed by his writing and turned to ask her subjects for the author’s name. It must have been the first time that Wu Zetian learned that this talented writer had been demoted to Linhai (in modern Zhejiang) after his two years’ service in the central government as Attendant Censor (Shiyushi 待御史). She said, “This is the prime ministers’ fault. How can they lose this person?”[5]

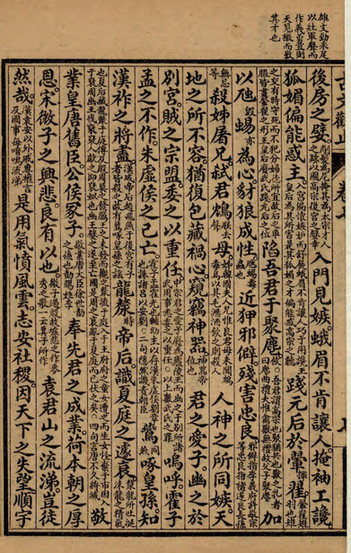

(Right to left) “Wei Xu Jingye tao Wu Zhao xi” 為徐敬業討武曌檄 from the Qing anthology Guwen guanzhi 古文觀止 (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1916)

Obviously, Zhang Tingshou saw something positive in Luo Binwang’s unsuccessful career at the court. As he suggested in his poem, Luo Binwang could not have written the denunciation that earns him eternal fame if he hadn’t been abandoned by the court and joined Li Jingye’s rebellion. Indeed, Luo Binwang remains a famous name well over a millennium after his death. But looking at the innocent boy depicted on every table at the restaurant, I started to imagine how surprised people like Zhang Tingshou might be if they found that, despite his subversive spirit, Luo Binwang is more widely celebrated for his lines on the goose.

[3] For a convenient reference for Luo Binwang’s original text, see “Dai Li Jingye chuanxi tianxia wen” 代李敬業傳檄天下文 (Denunciation to all under heaven on behalf of Li Jingye) at https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&file=36421&page=2. [4] See the works collected in the appendices to the modern edition of Luo Linhai ji jianzhu 駱臨海集箋注 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1985), annotated by Chen Xijin 陳熙晉 (1791-1851), 375-424. [5] See the Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&chapter=908552 (passage 14) and Xin Tanshu 新唐書: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&chapter=307663 (passage 58).

Copyright Declaration*:

The texts and images used on the website of Rachelle's Lab are either from the public domain (e.g. Wikipedia), databases with open data licences (e.g. Shuhua diancang ziliao jiansuo xitong 書畫典藏資料檢索系統, National Palace Museum, Taipei), online libraries that permit reasonable use (e.g. ctext.org), or original work created for this website.

Although fair use of the website for private non-profit purposes is permitted, please note that the website of Rachelle's Lab and its content (including but not limited to translations, blog posts, images, videos, etc.) are protected under international copyright law. If you want to republish, distribute, or make derivative work based on the website content, please contact me, the copyright owner, to get written permission first and make sure to link to the corresponding page when you use it.

版權聲明:

本站所使用的圖片,皆出自公有領域(如維基)、開放數據庫(如臺北故宮博物院書畫典藏資料檢索系統)、允許合理引用的在線圖書館(如中國哲學電子化計劃)及本人創作。本站允許對網站內容進行個人的、非營利性質的合理使用。但請注意,本站及其內容(包括但不限於翻譯、博文、圖像、視頻等)受國際版權法保護。如需基於博客內容進行出版、傳播、製作衍生作品等,請務必先徵求作者(本人)書面許可,并在使用時附上本站鏈接,註明出處。

*Read more about copyright and permission here.

Comments